| |

Home

Home

|

|

|

|

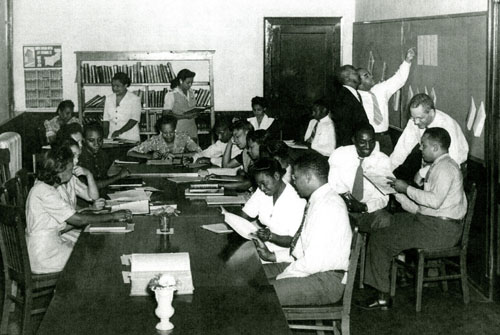

Cooperative Planning, Student Growth, and Building Community

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Laboratory High School graduate William A. Robinson Jr. described the practice of non-grading at the school and a curriculum reflecting a social-problems approach (an Alberty Type 4 core) with substantial independent study at a high academic level, a point noted as well by the art teacher, J. Eugene Grigsby. Governance of the school was determined through cooperation. In 1940, the Lab School staff was described as having met weekly during the past ten years, and “the experiments in curriculum and method carried on in this school have been the products and thought and planning of the staff, rather than of one or a few persons” (Bimson, et al., 1940, p. 351).

The science faculty distinguished itself at the national level. William H. Brown, who would lead the Secondary School Study after Robinson left the project, was the chemistry and physics teacher and would prepare science source materials that were distributed nationally. His curriculum was quite expansive; for example, in a fused core chemistry class students would explore photography and darkroom procedures (Brown, W., 1945b; Grigsby, 2010). Perhaps most intriguing is a 1941 article coauthored by Beulah Baley, the biology teacher, and Robinson entitled “Teaching the Beginning of New Life,” describing a realistic example of teacher-pupil planning for a problems-based biology course. Shifting from a “Morrison unit” curriculum, Baley and Robinson described classes where “pupil participation in the choice and planning of the units increased to the extent that finally the entire course was planned with their help, and subjects began to be studied which either were not broadly treated or were touched only slightly or not at all in traditional high school biology courses built on textbooks” (Baley and Robinson, 1941, p. 30). The article featured an innovative “new life” biology unit, addressing issues of co-education groupings without the problems of a sex education course and leading directly into the subject of heredity that, clearly, would have become the subsequent student-planned unit. |

|

|

Period comments about Atlanta University Laboratory School philosophy of education:

Excerpts from the “Point of View” of the Laboratory School:

“As one of the few Laboratory Schools at Negro universities we had the obligation to assume a leadership in experimentation in elementary and secondary education. This meant:

That we should seek to develop a sound philosophy of education based upon a clear understanding of the principles of psychology and of child growth.

That in all of our contacts with each other on the staff and with the children we should adopt sincerely and without artificiality the principles of democracy.

That our approach to behavior should be clinical and not punitive. This leads us to get rid of all routine punishment; to the case study approach to behavior; to more interest in changing the child’s attitude than in changing his behavior; to the conviction that all behavior represents learning or conditioning and, therefore, to the attempt to be as impersonal and unemotional in our approach to mistakes in ‘conduct’ as to mistakes in Algebra.

That we should examine our classroom techniques and alter or improve them where our study indicated.

We studied the ideas of Henry C. Morrison of Chicago University and began to experiment with the elimination of daily lessons and all practices built around them. We were familiar with the psychological principle that learners are more challenged by comprehensive and significant blocks of work than by small blocks but we had followed tradition and had not developed techniques for presenting our work in this way.

That there is no final best procedure but that we must continually be critical of our philosophy and of our procedures and alter them and improve them as experimentation and new knowledge may dictate” (Brown, 1944, p. 491).

Period comments about Atlanta University Laboratory School from students:

“I think we learn to take responsibilities here. Each student realizes that he is going to school for himself, and that if he is going to get an education, he will have to do it. One thing this school tries to teach us is cooperation. We learn how to discuss in our classes and we also learn how to plan work together. When we get out of school into life, we will have to be able to plan our own affairs. So while we are in school we ought to learn to plan for ourselves what we are going to do and how and why.” —A male student from Laboratory High School (Bimson, et al., 1940, p. 186)

“I had always been accustomed to doing what the teacher assigned me to do, but when I came here I had to learn to take my own responsibilities. I didn’t like this method at first, but now I have come to like it very much. I find that I have to please myself instead of pleasing the teacher. There is no one to tell me that I must do anything. After two or three weeks here, I found I was learning to plan my own work and to make better use of my time.” —A female student from the Laboratory High School (Bimson, et al., 1940, p. 186)

Bibliographic References:

Baley, Beulah L. and William A. Robinson (1941). “Teaching the Beginning of New Life,” Science Education 25:1, pp. 29-34.

Bimson, Oliver, W. G. Carr, S. Everett, G. L. Maxwell, and H. E. Wilson (1940). Learning the Ways of Democracy: A Case Book of Civic Education. Washington DC: NEA and the AASA.

Brown, Brown (1944). “An Evaluation of the Accredited Secondary Schools for Negroes in the South,” The Journal of Negro Education 13:4, p. 491 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

return to

Atlanta University LaboratorySchool

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|